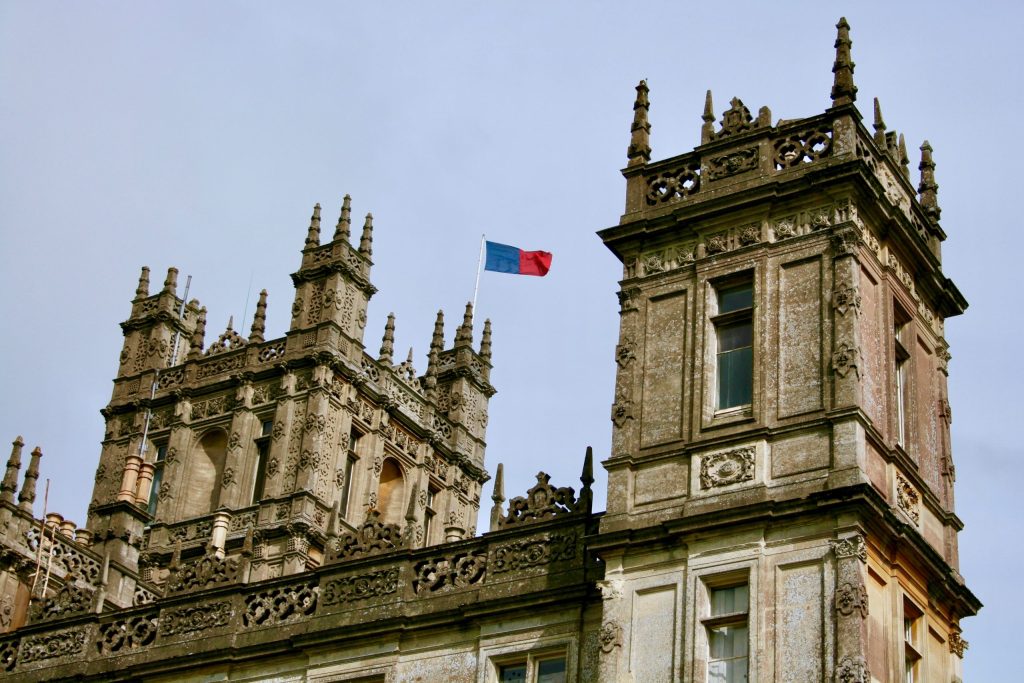

What do King Tut and Downton Abbey have in common? England’s Highclere Castle, the film site for the costume-drama TV series that airs on PBS and the Downton Abbey film.

What do King Tut and Downton Abbey have in common? England’s Highclere Castle, the film site for the costume-drama TV series that airs on PBS and the Downton Abbey film.

Highclere Castle is the ancestral home of the Carnarvon family, and during the early 20th century, the Fifth Earl of Carnarvon became fascinated by ancient Egypt when he traveled to its warm, dry climate for health reasons. Soon the Earl began to fund archaeological digs in Egypt—including Howard Carter’s excavations, which eventually resulted in the 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

In my last post about my visit to Highclere Castle, I didn’t say much about the Egyptian exhibit, so I thought I’d share some impressions.

First, this exhibit is modest compared to the one not far away at London’s British Museum, where you can see the Rosetta Stone. That said, at Highclere Castle, I felt a more emotional connection to the Egyptian artifacts than ever before—even when the King Tut exhibit came to Denver two years ago and I saw actual artifacts from the pharaoh’s tomb.

I believe there’s a certain intimacy—or maybe it’s history—you sense when you’re in a place with an actual physical connection to something or someone. Knowing I was standing in the same house where Lord Carnarvon and Howard Carter pored over maps of the Valley of the Kings—the greatest Egyptology discovery in history—gave me goose-bumps.

The Carnarvons: Avid Amateur Egyptologists

Highclere’s Egyptian exhibition is very personal for the Carnarvon family. The Fifth Earl’s family—especially his wife, Lady Almina, and their daughter, Evelyn—often accompanied him to Egypt and sometimes helped with excavations.

After reading Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey, written by the current Countess Carnarvon about her family’s ancestors, I felt a kinship with Almina. So it was delightful to see exhibited a beautiful calcite jar (dating to the reign of pharaoh Ramses II) that Almina helped dig from the ground.

(Or so the story goes. Wearing a corset and heavy, long skirts during the early 1900s, Almina’s contribution might have amounted to brushing off the last of the sand from the calcite jar after someone else did the painstaking hands-and-knees job of unearthing it. But I rather like the idea of Almina getting her hands dirty to excavate a jar that might have been held by an Egyptian pharaoh/god 3,200 years ago.)

Another exhibition highlight was a 3,500-year-old painted coffin of a 35-year-old noblewoman named Irtyru, that Carter and Carnarvon excavated from Deir el-Bahri in 1908. The paint on this wooden coffin was so brightly colored that it almost looked fresh. The feet on her coffin showed a lovely pedicure—rendered in gold paint.

The exhibition also displayed recreations of Tutankhamun artifacts, including a convincing reproduction of Tut’s mummy, wrapped in hieroglyphic-covered cloth with jewelry and amulets tucked into the folds. His mummy wears gold sandals, and each of his toes were encased in gold toe covers so that the boy-king could walk in the afterlife. (Tut died at about age 19; he was on the throne for nine years from roughly 1333 BC to 1323 BC.)

What stays with me about seeing these artifacts is their artistry, rendered with exquisite skill. Although we think of the ancient Egyptians as being obsessed with death, I started wondering if they weren’t really more interested with the afterlife. Pharaohs were buried with models of ships that would bear the departed king or queen on their journey across the sky to the afterlife.

Shabti figurines are among the artifacts discovered by the archaeologist Howard Carter, who was funded by Lord Carnarvon. Photo courtesy Highclere Castle

Figurines of workers were included in tombs; they accompanied the pharaoh into the afterlife so they could perform the manual labor needed to live for eternity in the luxury to which the royalty had become accustomed. (The pharaoh was not just a ruler but a god.)

At Highclere Castle, I noticed that these figurines had been created with sensitive, expressive faces. The artists didn’t fill the tombs with work they cranked out for the masses; they did their best work—even though Tutankhamun died suddenly and unexpectedly, probably of an infection from a fractured leg. Tut had a genetic bone disorder and probably other genetic defects, because Egyptian royalty were famous for marrying close relatives, often siblings. (Tut himself married his half-sister.)

Seeing history through the lens of the Carnarvon family was exciting. Lady Evelyn was the first woman to step into King Tut’s tomb, as she accompanied her father to Egypt in November of 1922 when Howard Carter wired about his find. (Due to illness, Lady Almina was unable to travel for the tomb’s opening.)

The Story of the Pharaoh’s Curse

After Carter and Carnarvon opened Tut’s tomb, the event became a media circus with enough drama that it would have rivaled the Lady Mary/Mr. Pamuk sex scandal on Downton Abbey.

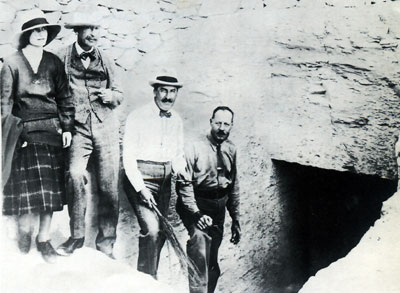

At the entrance of King Tut’s tomb in 1922 (from left to right): Lady Evelyn Carnarvon; her father, the Fifth Earl of Carnarvon; archaeologist Howard Carter; Carter’s assistant.

The discovery of the tomb was followed by many squabbles among the English archaeologists, accusations (unproven) that Carter and Carnarvon stole artifacts from the tomb, rumors that Lady Evelyn was enamored with Howard Carter, and bitter fighting between the Egyptian government and Carnarvon and Carter about who owned the tomb’s treasures.

And then there was death of Lord Carnarvon, less than five months after the Tut discovery, which fueled the legend of the Curse of the Pharaoh. In reality, Carnarvon was bitten by a mosquito on his cheek and nicked the bite while shaving. The wound got infected, and Carnarvon became seriously ill from blood poisoning. Weakened, he contracted pneumonia and died in Egypt in April of 1923 at age 57. Supposedly, the lights went out in Cairo when Carnarvon died. And there’s a story that at the same moment in England, the Earl’s pet terrier howled and dropped dead. Thus the hysteria over Mummy’s curses mounted.

Wonderful Things to See

This all goes to prove that the true stories of people can be more compelling than fiction—and in the case of Highclere Castle, they added layers of color to my visit there.

The current Countess Carnarvon in the Egyptian exhibition at Highclere Castle. Photo courtesy Highclere Castle

Would I have enjoyed a tour of the historic house if I didn’t care about Egyptology or had never seen Downtown Abbey? I’m sure the beauty of the Saloon, Library and Music Room would have impressed me, but aside from that and the magnificent exterior of the building, would Highclere Castle glow in my memory? Because I had read the Lady Almina book, am an Egyptology buff, and became passionate about the PBS series, the halls of Highclere were alive and filled with wonder.

Our glimpse into the treasures of this English estate house brought to mind the famous quotes from Howard Carter and Lord Carnavon when they first opened King Tut’s tomb. As Carter chiseled a hole in the sealed entrance and peered in, Carnarvon asked, “Can you see anything?” Carter replied with the famous words: “Yes, wonderful things.”

—Laurel Kallenbach, freelance writer/editor

Originally posted April 2013

Updated September 2019

Read more Downton Abbey posts:

- My Pilgrimage to the Real Downton Abbey

- An Eco-Elegant English Hotel, “Downton Abbey” Style

- Bampton, England: Film Location for “Downton Abbey”

- Sweet Dreams at Downton Abbey

Highclere Castle’s spires in 2012: Ninety years after the discovery of King Tut’s tomb. © Laurel Kallenbach

Now I know why we’re friends; I was obsessed with Lord Carnarvon as a little girl, too!

Ah, I didn’t know you were a fellow Egyptian buff! Funny how these synergies happen.

Okay, so I bought the book becsuae I’m a die-hard Downton Abby fan, but from the moment I opened the book, it was all about Lady Almina. There are many similarities in the historical elements of both this book and the tv series, but the personal stories are quite different. Lady Almina did set up a hospital at Highclere Castle (which is the setting for the series) but her hospital was up and ready when the first casualties returned to England. And, everyone in the family was supportive and doing their share to help the wounded recover. Although I did know that World War I was horrific, I had only seen the American perspective. Looking at the war through British eyes showed the true magnitude of slaughter. Shell shock has a whole new meaning to me now.Lady Almina’s husband, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, bankrolled the expeditions that led to the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922. Lord Carnarvon didn’t just provide the funding for the expeditions, he and Lady Almina spent many winters in Egypt overseeing the operations. The book is fascinating and difficult to put down. It is beautifully written by Lady Fiona, the current Countess of Carnarvon, and the photographs are a delight even in a ebook. You might also enjoy the book’s , where you’ll find several short clips of Lady Fiona talking about the book and the family.

Loved the top 10 Maggie moments! And I relaly enjoyed the first episode of the new season (can’t wait to see the rest!). I agree with you there’s something about Brendan Coyle (aka Bates) that just gets me. He always plays a good guy with a very strong moral code. I love him on Lark Rise to Candleford (if you haven’t seen that, I highly recommend it).I’m so glad they are having a third season! From what I’ve heard, it takes place from 1920-21, so it doesn’t cover quite as much time as the other two do.

Interesting, thanks.

Jan Summers

Egyptologist, Archaeologist

KV63, 62