If you’re visiting Washington, D.C. for the Women’s March—or for any other reason—be sure to leave time to bask in the vibrant National Museum of Women in the Arts, an entire building devoted to female-created paintings, sculpture, photography, book-art, multimedia art, and film through the centuries.

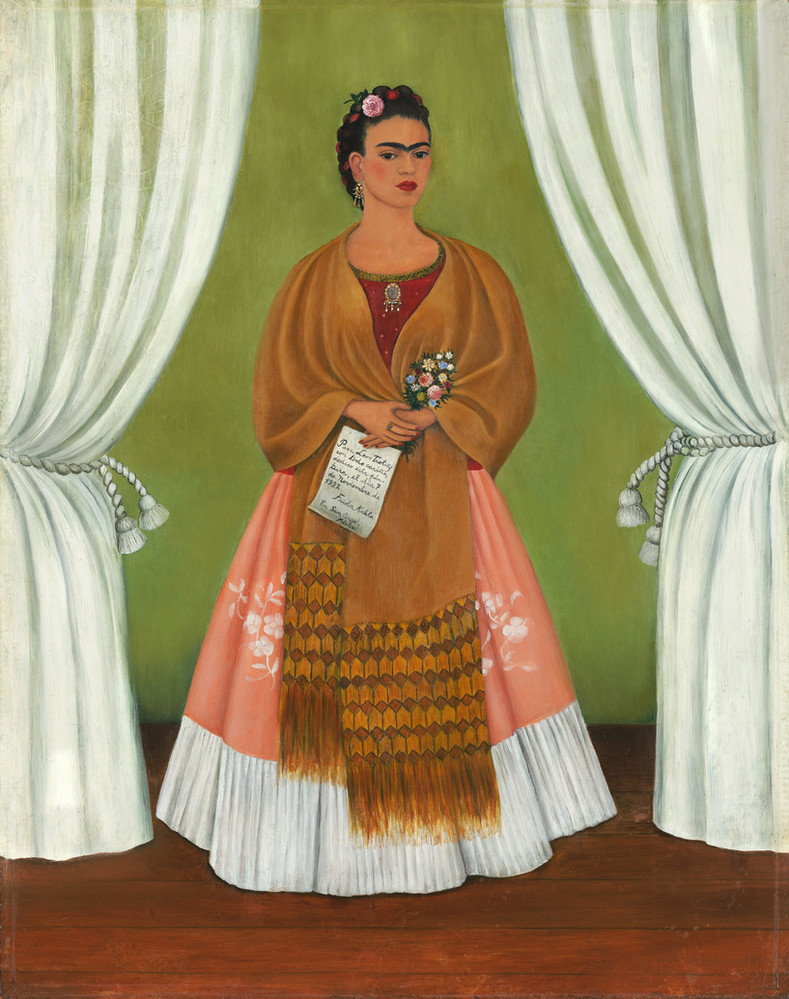

Closeup of Frida Kahlo’s “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky.” Read details below. ©Laurel Kallenbach

A few blocks off the National Mall, this art museum for women is a gem—and it doesn’t attract the huge crowds that the Smithsonian Museums do, which makes it pleasant—even so, I wish this museum were better known.

Every time I’m in Washington, I set aside time to visit and see some of my favorite permanent pieces as well as the unique temporary exhibitions.

I also support this museum by buying an annual membership, which gains me free access. The National Museum of Women in the Arts is, after all, the first museum in the world dedicated exclusively to recognizing the achievements of female artists.

With its many collections, special exhibitions, and educational programs, the National Museum of Women in the Arts advocates for better representation of women visual artists. It also addresses the gender imbalance in the presentation of art by bringing to light important women artists of the past—while simultaneously promoting the talented women artists working today. NMWA’s collections feature more than 5,500 works from the 16th century to today created by more than a thousand artists. The collections encompass work in many mediums, featuring paintings by Lee Krasner, Berthe Morisot, Faith Ringgold, Amy Sherald, Alma Woodsey Thomas, Suzanne Valadon, and Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun. Also in the collection is sculpture by Magdalena Abakanowicz, Sarah Bernhardt, Chakaia Booker, Louise Bourgeois, Judy Chicago, Dorothy Dehner, Barbara Hepworth, and Louise Nevelson. In addition, there are works on paper, photography, and video art.

Read on for some more highlights from one of my recent trips to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in our nation’s capital.

Judith Leyster (1609–1633)

Yes, you read the dates correctly! Judith Leyster was a Dutch woman who lived before Vermeer and was a contemporary of Rembrandt. Leyster established her painting career independently and was the first woman admitted to Haarlem’s prestigious Guild of St. Luke.

Leyster was also the first woman to maintain a workshop with students and to actively sell art on the open market. In The Concert (pictured here), the sitter on the left has been identified as her husband, and the central figure may be the artist herself.

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954)

Like many Mexican artists working after the Revolutionary decade that began in 1910, Kahlo was influenced in her art and life by the nationalistic fervor known as Mexicanidad.

“Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky” by Frida Kahlo, 1937; oil on masonite in the National Museum of Women in the Arts

The artists involved in this movement rejected European influences and favored a return to the country’s native roots and folk traditions.Kahlo often wore the distinctive clothing of the Tehuantepec women in southwest Mexico; she also looked to pre-Columbian art and Mexican folk art for forms and symbols in her paintings.

The compositional elements of the stage and curtains, for example, draw upon Mexican vernacular paintings called retablos, devotional images of the Virgin or Christian saints painted on tin, which Kahlo collected.

Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (1937, oil on Masonite) commemorates the brief affair Kahlo had with the exiled Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky shortly after his arrival in Mexico in 1937.

In this painting, she presents herself elegantly clothed in a long, embroidered skirt and fringed shawl. She holds a bouquet of flowers and a letter of dedication to Trotsky that states, “with all my love.” Although this isn’t one of Kahlo’s more visceral images, it’s still amazing to see the work of the great maestra.

Remedios Varo (1908–1963)

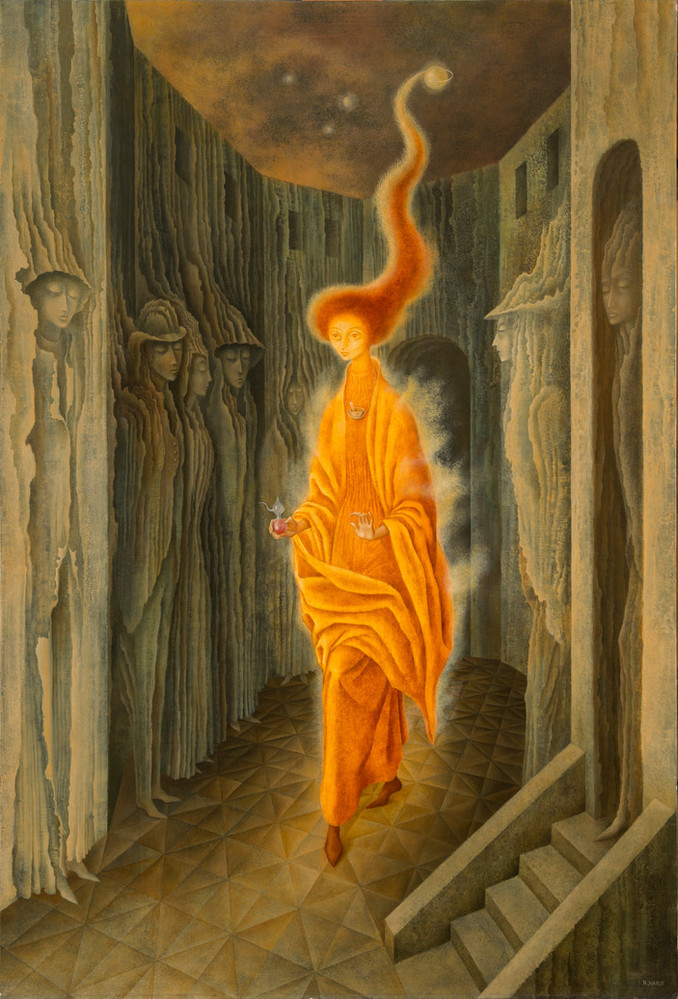

Remedios Varo, “La Llamada” (“The Call”), 1961; oil on masonite, National Museum of Women in the Arts. Photo by Lee Stalsworth

One of my favorite painters of all time is the Spanish/Mexican Surrealist, a woman named Remedios Varo, who fled to France to escape the Spanish Civil War and then left France for Mexico during WWII, when modern artists were persecuted.

In Mexico, Varo remained friends with fellow refugees from her European Surrealist circle, including artist Leonora Carrington, who became her closest friend and collaborator.

This painting, La Llamada (The Call) hangs prominently in the National Museum of Women in the Arts and is my favorite of all her works. Because of this work, visiting the museum is always a bit of a pilgrimage for me—a chance to experience her vision firsthand. (In the early 2000s, the museum had a temporary exhibition of about 30 of her works, and I flew to Washington, D.C. especially to view that show.)

Like many figures in Remedios Varo’s paintings, the subject of The Call (1961) is intensely and solemnly focused, as though she is in the middle of an adventure or some kind of quest. Wearing flowing robes and carrying alchemical tools, including a mortar and pestle hanging like a necklace, she traverses a courtyard. Her hair forms a brilliant swirl of light, which seems to bring her energy from a celestial source.

I love how the woman in the painting is illuminated in fiery, orange-gold tones, and how she walks fearlessly and purposefully past the shadowy men entombed in tree bark.

I feel like this woman has a creative spark—in fact, she is herself a creative spark connected to the heavens—and she seems determined to follow her own magical creative path, undaunted by the onlooking men.

Remedios Varo created this work near the end of her life, while living in Mexico where her artistic reputation was growing. It reflects her Surrealist influences and her interests—she dabbled in alchemical experiments—as well as her talent for evoking a psychological dream world and ambiguous narratives through her art.

I have small prints of several of Varo’s paintings and a refrigerator magnet that I bought at the museum when I visited. Exploring the Sources of the Orinoco River depicts a woman in a Surrealist boat that looks like a fish/overcoat. She has arrived at the source of the Venezuelan River, where there’s a chalice with clear water flowing from it—bringing to mind the Holy Grail. It’s full of magic and

Faith Ringgold (b. 1930)

When I walked into the room with this seven-foot wide creation, I couldn’t help but smile. It’s the bold and lively creation of Faith Ringgold, who trained as a painter but originated the African-American story-quilt revival in the late 1970s.

This piece, Jo Baker’s Bananas (1997), depicts Josephine Baker, the famous American entertainer who became a stage legend in France where she lived most of her life. Baker’s figure is represented five times across the top, implying movement across a stage. The so-called “Banana Dance” that Baker performed in 1926 at Paris’s Folies Bergère music hall cemented her fame.

Off stage, Josephine Baker used her fame to support the burgeoning Civil Rights movement in the United States. In August 1963, she was the only woman to speak at the March on Washington, where Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his “I have a Dream,” speech. Josephine Baker spoke passionately against discrimination, drawing from her own life experiences and painful memories of segregation in the US.

Jo Baker’s Bananas is actually an acrylic painting on canvas, but the border is quilted. Don’t you love the color and movement in Ringgold’s creation?

Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923)

“After the Storm” by Sarah Bernhardt ©Laurel Kallenbach

Internationally known as an actor in 19th-century Paris, Sarah Bernhardt was also an accomplished sculptor.

Bernhardt witnessed a Breton woman holding her dying grandson, who had become fatally entangled in his fishing net. She immortalized that scene in her poignant sculpture titled After the Storm.

She chose a classical composition that recalls the Pietá by Michelangelo, in which the Virgin Mary cradles the crucified Christ. Done in marble, Bernhardt created this piece around 1876.

Passionate about all forms of art, Bernhardt also painted, designed dresses, directed a theater company, and supervised the sets and costumes for her productions. She was famous for her debut in Racine’s tragedy Iphigénie, which helped make her an internationally famous stage actress. She exhibited her sculptures in Paris, London, New York, and Philadelphia, and in the World’s Columbia Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900.

Maria Martinez (1887–1980)

For years I admired the shiny-black Native American pottery I saw when visiting New Mexico, but only a decade ago did I realize that most of it was created by a woman who lived in the San Ildefonso Pueblo, a community 20 miles northwest of Santa Fe.

Maria Martinez learned to make pottery from her mother and grandmother, and she became legendary in the Southwest, especially for her black-on-black pottery.

Although this ancient pottery style had been used by the ancestors of the Pueblo people, the knowledge of how to create it had been lost over the centuries. Through study and experimentation, Maria and her husband, Julian, perfected their process for making the unique, beautiful black pottery in 1921. Throughout her life, Martinez collaborated with a number of members of her family, all of them becoming unique artists in their own right.

Because of the work of Maria Martinez, Puebloan traditions continue to thrive today, helping preserve the heritage of this often female-made art form in an era when clay pots have been replaced by modern cookware.

Polished blackware pottery with matte slip paint (circa 1939) by Maria and Julian Martinez. ©Laurel Kallenbach

The photo of Maria Martinez (above) is by photographer Laura Gilpin (1891–1979), who created a female vision of the American Southwest, which was typically depicted as a masculine place of rugged conquest. She and Martinez were longtime friends, and much of her work highlighted the native people and art-making traditions of the American Southwest. She distinguished herself as a platinum-print photographer, and her work appears in museums around the world.

Lee Krasner (1908–1984)

I love how the curators at the National Museum of Women in the Arts juxtaposed the two pieces of art shown below. The painting on the wall that combines circles, ovals, and chevron shapes is by Abstract Expressionist painter Lee Krasner. Her canvas is titled The Springs (1964), which refers to the village near East Hampton, Long Island, where Krasner and her husband, artist Jackson Pollock, moved in 1945. After his death in 1956, Krasner began using the small barn on the couple’s property as her studio. The nature-based hues in The Springs, along with its arcing lines and interlaced forms, are reminiscent of a wind-blown landscape.

Frida Baranek (b. 1961)

The Brazilian artist’s Untitled sculpture (1991) looks as if it were flying in the wind. Though it appears to be light, Baranek’s sculpture is actually made of rusted iron wire and rods—and it weighs about 90 pounds. The museum notes that the interweaving of wire and rods gives the sculpture a linear quality, as if it were a “drawing in space.” Baranek is interested in using her art to comment on environmental issues in her native Brazil and globally.

Polly Apfelbaum (b. 1955)

Inspired by Andy Warhol, Polly Apfelbaum often incorporates flower forms into her compositions. The custom-carved woodblocks made for her flower prints—this one is titled Love Alley 4—are based on her hand-drawn doodles and printed on handmade paper.

—Laurel Kallenbach, freelance writer and editor

Originally published January 2019

What a great article! I’ve learned so much and can’t wait to visit this wonderful place the next time I’m in DC. Thanks for sharing, Laurel!

Thanks so much for reading!

When I visited, I felt tears in my eyes that there was all this superb art by women artists and I lingered and loved it!

Yes, I too had several times of choking up while at the museum. All the art the world has never seen or written about or debated or enjoyed. Just because it was created by a woman. And don’t even get me started about all the women who WANTED to create art but couldn’t because they thought they were inferior or that had children to raise or that all their energy went into supporting fathers, husbands, brothers.

So true, Laurel. Thanks for this lovely reminder–can’t wait to go back!

Love that place!

Great article Laurel. I will put this museum on my list for my next visit to DC!

Glad you liked it. Right now the museum building is being renovated, though there are virtual exhibits and online events on their website. Not sure when the building will open again.