Originally posted February 2017

February is not the most popular month to visit Dresden—the glittering Christmas Market is long gone, and there are no summery flower boxes or outdoor cafés. But for music and museum lovers like me, winter is a thrilling time to visit this musical city.

Dresden’s Semper Opera House on the Theaterplatz. Photo by Christoph Muench, courtesy Dresden Marketing Board

One of my primary reasons to travel to Dresden was to attend a performance in its world-renowned Semper Opera House, which simultaneously juggles at least three operas, a ballet, and orchestra concerts during the winter months. Before I departed in early February, I peeked at a map of Dresden’s historic Old Town (Altstadt) and was thrilled that the opera house located in the heart of the historic city.

In fact, the entire square, the Theaterplatz, is named for the venerated opera house. Dresden’s Old Town contains many architectural and cultural gems, and some of the most spectacular are concentrated in the Theaterplatz, including the glorious Rococo-style Zwinger Palace, home to several fantastic museums.

Though there are many other gorgeous and historic buildings and churches to enjoy in Dresden, you can’t go wrong starting in Theater Square. There were three sites in the Theater Square that I particularly enjoyed: The Zwinger, the Old Masters Picture Gallery, and the opera house itself.

1. The Zwinger

What’s a “zwinger”? The word sounds like a hip nightclub, and back in the early 1700s when it was built, Dresden’s Zwinger was indeed an 18th-century party venue for the aristocracy.

Sculptures at the Zwinger Palace ©Laurel Kallenbach

“Zwinger” is an Old German word that refers to an area between a castle’s walls and the outer fortress walls. Dresden’s ornate Zwinger, often called the Zwinger Palace, was originally designed as an orangery and a setting for court festivities. It was later used for exhibitions; today it houses several museums.

Dresden’s Zwinger Palace is known for its beautiful baroque architecture, which, as you can see from the photos, means there are lots and lots of showy arches, curlicues, floral motifs, fountains, walkways, and Greek-inspired statutes.

The porcelain bells mounted in the Zwinger Glockenspiel Pavilion chime on the half-hour. ©Laurel Kallenbach

The Zwinger is an ideal place to stroll on a nice day—and it’s free to the public. At the southeast end of the Zwinger’s courtyard is the Carillon/Glockenspiel Pavilion with a collection of white glockenspiel bells made of porcelain by the famous Meissen factory. The bells play a tune every half-hour, which usually attracts a bit of a crowd.

The Nymph Garden and Crown Gate are filled with enchanting mythological sculptures and fountains (which were dry during my visit in February). Nevertheless, it was wonderful to behold the statues, though I shivered inside my toasty down coat because the sculptures had no warm clothes to protect them from the winter weather.

Ice-cold statues of naked goddesses in the Zwinger Palace ©Laurel Kallenbach

I would have loved to linger in the Zwinger for longer than I did, but a chilly wind was blowing, and all the unclad goddesses made me feel even colder. I vowed to return to Dresden in summer, when flowers and fountains and weather would be brilliant.

Luckily, the Zwinger Palace houses wonderful museums (entry fees apply): the Dresden Porcelain Collection, the Mathematics and Physics Museum, and the Old Masters Picture Gallery. It was into this last museum that I hurried in to warm up.

2. Old Masters Picture Gallery

This museum, in the Semper building adjoining the Zwinger, contains one of the world’s most important collection of paintings dating from the baroque and Renaissance period. The 700-piece collection was started 300 years ago by Augustus II the Strong, who built the Zwinger, along with a lot of the baroque structures in Old Town Dresden, the capital of Saxony.

Raphael’s “Sistine Madonna” at the Old Master’s Gallery

The most famous painting in the Old Masters Picture Gallery (Gemäldegalerie Alter Meister) is Raphael’s “Sistine Madonna,” which I wanted to see in part because of the two comical cupids at the Virgin’s feet. Their image is so popular that it appears on refrigerator magnets, greeting cards, and blank journal books. Yet, they’re only part of the appeal of the painting: the deep colors were amazingly vibrant, and the shading in the folds of the clothing and drapes was truly astonishing.

Apparently the exasperated cherubs’ fame has also reached the Far East, because when I arrived in the chamber with the wall-sized Madonna, a group of Japanese tourists was getting their pictures taken in front of the painting—first individually, then in pairs, and finally many different exposures and arrangements of the entire group at once. I wanted to get closer to the painting to see the cherubs in detail, but I didn’t want to spoil anyone’s pictures. The photo session took so long that I gave up and continued on to enjoy some other art.

The Renaissance painters, Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) and his son Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515–1586) were also incredibly gorgeous. Paintings by the younger Cranach were so detailed and realistic that they looked more like photographs than oils.

I was enthralled by Cranach the Younger’s “David and Bathsheba,” which focused on the bathing Bathsheba surrounded by her handmaidens, one of whom has turned and stares straight at the viewer. Though the scene is biblical, the women were dressed in Renaissance garb. Initially, I thought the painting was mis-titled because King David was nowhere to be seen. At the last minute, just when I was moving on to look at the next painting, I spotted a man wearing a crown high in a castle tower in the upper left-hand corner of the painting. King David was almost completely out of the picture due to his distant location, but we could still see him staring lustily at the married Bathsheba from afar! Was he already plotting how to get rid of her husband?

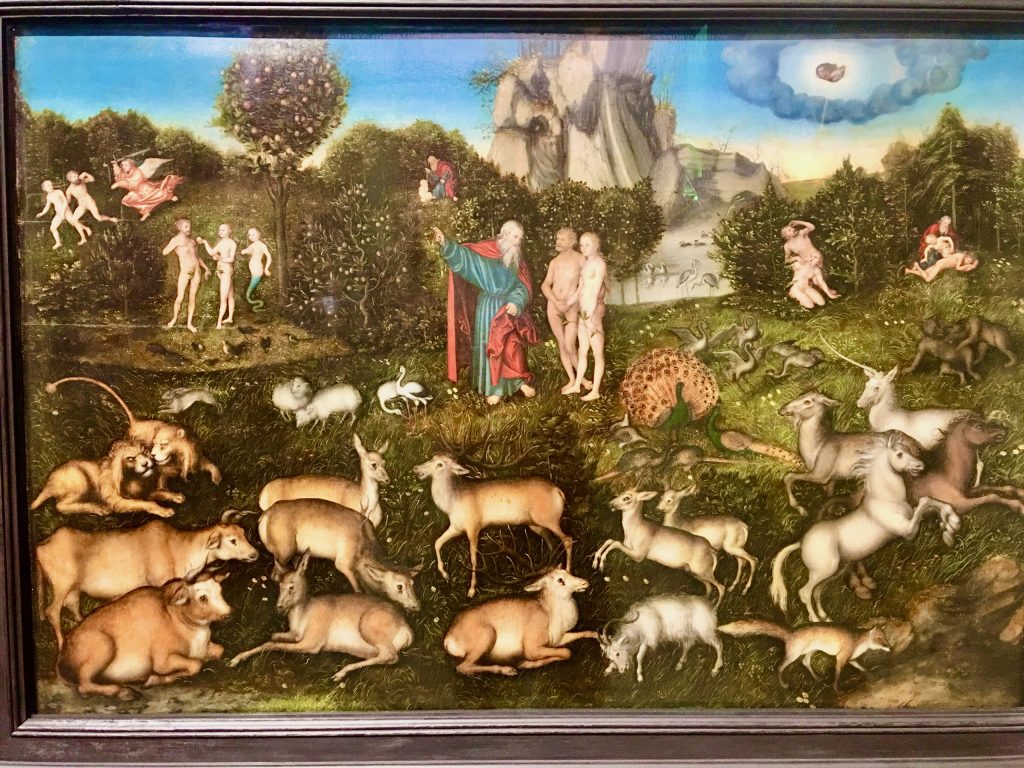

“Paradise” by Lucas Cranach the Elder hangs in The Old Masters Picture Gallery in Dresden. (1530, oil on wood)

Cranach the Elder’s depiction of the Garden of Eden accentuated pairs of animals, including unicorns (on the far right). Adam and Eve are in the background; that story is overly told, but the animals in Paradise were a refreshing twist.

It would have been easy to spend a couple of hours in the Old Masters Gallery, but I had just an hour. With more time, I would have looked up Vermeer’s “Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window”—and maybe I would have returned to the Raphael “Madonna” when there were fewer people.

3. Semper Opera House

As a musician, I was drawn most of all to the iconic Semper Opera House, which for me is a temple of music—the equivalent of visiting a great cathedral. Even if you’re not an opera fan, the opera house is worth touring for its stunning architecture and ornate interior. It’s also home to the Saxon State Opera, the Saxon State Orchestra, and the Semperoper Ballet.

I took a 45-minute tour given in English of the magnificent building, during which I learned about its three incarnations. Originally built in 1841 by architect Gottfried Semper, the opera house wowed audiences throughout Europe. The brilliant (and anti-Semitic) composer Richard Wagner was one of its early music directors. Three of Wagner’s operas premiered at the Semper Opera House: Rienzi, The Flying Dutchman, and Tannhäuser.

Unfortunately, the opera house burned down in 1869 and didn’t reopen in its full glory until 1878, when it was reconstructed according to another of Semper’s designs.

A beautifully decorated ceiling at the Semperoper with Apollo and his swan. ©Laurel Kallenbach

The second opera house was almost entirely destroyed during the bombing of Dresden in 1945. It took 40 years to rebuild, but in the 1980s, restorers painstakingly recreated nearly every detail of the former structure—plus they added more comfortable seating with better sight lines, modern heating/air conditioning, and state-of-the-art stage machinery.

When I walked through the halls and beheld the elaborately painted ceilings, the chandeliers, and the statues of singers and composers, I understood why the acoustically excellent Semper Opera House is also consideed one of the world’s loveliest. Though the 1980s reconstruction took place under the East German communist government, attention to detail was perfect, although many of the special craftsmen who knew how to create such wonderful finishes were gone.

At intermission, I strolled through the chambers of the Semper Opera House and marveled at the columns and vaulted ceilings—all rebuilt after the WWII bombing of Dresden. ©Laurel Kallenbach

The balustrades are made of serpentine stone, and the green “marble” pillars are actually built from brick covered with plaster, glue, and paint—then polished so that they gleam like marble. The giant chandelier in the theater weighs 1.9 tons and can be lowered from the ceiling so that it can be cleaned and its 258 light bulbs changed.

My guide took the tour group into the theater, where stagehands were preparing for the next show. They attached scenery to the stage’s fly system, and the orchestra pit had been raised to stage level so that they could roll in the celeste for the night’s performance. (A celeste is keyboard instrument that plays the glockenspiel part for the character of Papageno in Mozart’s The Magic Flute. (Most people are familiar with the celeste’s best-known solo, “The Waltz of the Sugarplum Fairy” in The Nutcracker ballet.)

A pre-show view of “The Magic Flute” at the Semper Opera House ©Laurel Kallenbach

That night, I attended The Magic Flute performance at the Semper Opera House, a beautifully sung production set in a modern fantasyland that was half Edward Scissorhands and half Pee-wee’s Playhouse. The theater was packed; the Germans really support the opera with enthusiastic attendance.

From my seats in the 1st Ring, I could see and hear wonderfully, and the supertitles—the lyrics projected above the stage—were in both English and German, so it was easy to know what the characters were singing.

Most notable was the Queen of the Night’s aria, a stratospherically high and notoriously difficult part sung by a coloratura soprano. The performer’s mouth opened wider than I’ve ever seen before, but her pitches were bright and true. It was breathtaking, and the applause was thunderous when she finished. Attending an opera in the spectacular Semper Opera House was an unforgettable experience.

—Laurel Kallenbach, freelance writer and editor

Yes Karen Heavrin, it is a shame “nothing” historical ever happened there!